Just some scribbles, nothing here is publishable.

A few starting intuitions about our present technological situation:

– we can largely disregard our physical environment;

– ours is a digital world;

– we can embed almost every rule in an artifact (you do not eat if you do not wash your hands – we can easily embed this rule in a virtual world, but we could do the same in real life; almost everything can get a sensor);

– breaking the rules is hacking

– DRM, GPS, CCTV, scanning doors, ATMs etc.

– we do not modify nature, we do not turn rules into natural laws, we put our concepts to work; we made our concept of calculus into a machine (however, we have made concepts into machines a long time ago);

*

I fold an origami bird automatically, while talking on the phone. I leave it on the table. Someone else takes it and uses it as a bookmark. It seems to be an artifact although it was not produced with the intention to be used in a certain way and it is not used according to the way in which it is regularly used (as a decoration). Proper intentions (at least as psychological acts) can be missing from this picture. My origami bird would still be an artifact. Why is this so?

Perhaps it is enough to regard the unfolded paper as a raw material and the origami bird as a product. What happens if we take the object out if this conceptual space? I draw some dots on a piece of paper while talking on the phone. There is no raw material and no product. This is similar to breathing. The air in my lungs does not become a product. I am using it to keep living, but this not the same meaning of “use”. It keeps me alive but I do not use it in order to reach the aim of being alive. Nobody needs to use the origami. It has an use as a decoration. The second person gives it a different use, but that might just change the type of the artifact it is, not its “property of being an artifact”.

What if I make something as an experiment, in order to explore its possible uses. I do not know how it can be used. I start from some raw materials, but I do mot have a proper use. So I am not still sure that mine is a product or an unsuccessful attempt to create a product. Then it is not an artifact, although it can become one if I find it an use. It was produced with the intention that one would find an use for it, but that does not make it into an artifact.

On the other hand, I can of course find an use for a tree. I can use to climb to the roof of my house. I can use it, so to speak, as a ladder. It is still a tree, and not a product, because it never went through the stage of being a raw material out if which I made something. When I find a strange looking broken branch and decide to use it as a decoration I regard it as a raw material out of which I could make a decoration. Then I can decide to use it as a decoration without further modifications. It becomes the final product without any additional action on my part, except this one – taking it from the class of raw materials and putting it into the class of final products (we can call this a conceptual act). “So the tree in my courtyard can become an artifact without me doing any physical action?” Indeed. If I were to think that I could cut down some of its branches in order to climb it more easily (that is, to regard it as a raw material out of which I could make something like a “natural ladder”) and then decide that there is no branch that I really need to cut down, then it might become and artifact.

“Why do you say ‘might’ instead of ‘would’?”

Because of the phrase “natural ladder”. I can put my cat on my shoulders and pretend it is “natural fur”. That does not make my cat an artifact. The cat gets an use (albeit a weird one) but I want it to remain “a part of nature”. This is, however, a special case (although, not such an uncommon one – we can keep Christmas trees in pots).

On a side note, the food in my stomach is no longer an artifact (although it is not yet waste) while cat food is an artifact because we use it to feed the cat, not because the cat eats it.

So x is an artifact IFF x was made into a product from a raw material (the third stage, that of waste does not seem necessary – works of art and concepts never turn to waste, but they are still artifacts).

Now we may ask:

(a) What is a productive action? (being made into)

(b) What does it mean for something to be a raw material?

(c) What does it mean for something to be a product?

Let us start with (c):

x is a product IFF x has a conventional use and x is the result of a productive action; x has a conventional use IFF there are some rules for the use of x which warrant that a purpose p is attained by using x.

(a) A is a productive action IFF A is performed by an agent and A falls under a description which specifies that the result of A has a conventional use;

(b) x is a raw material IFF x is conceived as the starting point of some productive action;

So, what is it for an artifact to embed a rule?

Let us say that x embeds a rule if the rules for x’s use are apparent from the physical properties of x (I do not say that x cannot be used otherwise because we can hack x – using an origami bird as a bookmark is not hacking, but picking a lock is, in a sense). If we want to be able to speak of hacking a concept we might drop “the physical properties of x” and use “the conceptual structure of x” instead. This might complicate things, though.

So what does it mean that a rule (for the use of an object) is apparent from an object’s structure (physical or not)?

Suppose that instead of writing “this side up” on a box I make the box with a pointed end on the side which I want to stay up, so that one cannot turn the box on that side. I embed the rule in the physical structure of the box. The box cannot be turned on that side because it will not stay on that side. It cannot support itself on that side (of course, one could flatten the pointed tip and keep the box on that side – that might be called hacking).

*

[something is an object of some intention – to classify, to observe, to describe, to explain, to theorize – as seem to be natural objects; to make use of – this might be a raw material; to use it for p – this is the artifact; to care for, communicate to, to love or hate, to aim at etc.

art and philosophy both push some boundaries; one might, as an artist, produce a musical piece during which the orchestra players must pretend they are tuning their instruments; a philosopher could imagine this while she tries to conceptualize collective intentions; a poet might use a proper name as a verb, while a philosopher if language must imagine such an use (for certain purposes)]

*

– we need to be able to apply the concept of raw material to something in order to be able to talk about something as an artifact (or a technological object) – so my analysis might include some pragmatically mediated semantic relations after all;

– being able to recognize raw materials is an ability (or a practice) necessary for being able to distinguish artifacts from non-artifacts (no raw materials were used to create a trail in the woods, but some were used in the creation of a city – however, in order for the city to be an artifact we must consider it the result of some collective productive action)

– being able to recognize or attribute uses is also a necessary ability for thinking or saying that something is an artifact (and also for saying that something is a raw material or a productive action [hacking, making adjustments, maintaining an object, repairing it, measuring, observing, consuming it a.s.o. are not productive actions; re-conceptualizing a raw material as a product, by recognizing it’s use or uses, adjoining part into a composite, detaching a part from a whole (in the right context), converting something into something else, subtracting some unwanted part etc. can make a productive action; packaging is not productive in a different way than the one in which adjusting is not productive);

25.12.2013

Let me try to think about this one more time. What is my conceptual proposal?

– First, I want to say that the distinction between artifacts and natural objects is not important for our concept of an artifact. There are contexts in which one has to do with nature – when one is engaged in scientific research, let us say. Now, even in this case, some would suggest that a scientist does not study nature, but produces data. Natural phenomena are the raw material, let us say, out of which the scientist produces experimental results, meant to be used, in turn, in the production of new theoretical concepts (and entities) – atoms, viruses, electromagnetic fields a.s.o. However, I do not want to enter into any science war. Heidegger’s essay on technology suggests that we do not live in a natural environment anymore. We cannot really regard anything without having it in view as a raw material, out of which something should be produced. We do not have mountains, but rocks in storage. This does not need empirical justifications. He proposes a change in the way in which we conceive ourselves. I think he is basically right, but I do not want to talk about this right now.

The concept of an artifact is related to our concepts of production and use. Natural objects, in this respect, can be used without being viewed as the result of a productive action (even if they are – a Christmas tree in a pot, to be decorated on the Christmas day and planted afterwards in the woods is still the result of a productive action; however, due to an ecological trend it is viewed as “a part of nature”). In short, there are natural objects of this sort because they are intended to be non-artifacts. Here the basic concept is that of an artifact, while the concept of a natural object is dependent on it. When I interact with my cat or with other people I do not think that they are natural objects. When a peasant says that it is going to rain, because the birds are flaying low, she does not make a prediction based on a scientific observation. She rather interprets the birds’ behavior, makes it part of a story, the moral of which is well known: rain will come.

So I do not think it would be of any use to try and distinguish artifacts from natural objects. One does not attempt to distinguish numbers from human values. They come in play when we are engaged in very different activities. To this one could reply that scientific and technological endeavors are related. Counting or calculating can be related to giving value to something (in a sense), but they belong to extremely different activities. Value concepts do not embed anything numerical. We can say that A is more valuable than B, but the request to specify “by how many times is it more valuable” seems absurd. Functional properties of our artifacts might depend on their physical properties, but they belong to an entirely different conceptual structure. For instance, I have strong doubts that one could measure functional properties. Commercials might tell us that some detergent washes three times more clothes than another, but they cannot tell use how many times is a detergent “better for washing” than another.

To conclude, I would say that something is an artifact not because it is not a natural object, but because it figures in a story in which we talk about raw materials, products, uses, waste, productive actions, repairing, adjusting, hacking, disposing of something, recycling a.s.o.

– Second, I think it is important to distinguish artifacts from raw materials and waste without talking about intentions as psychological entities. To do this we only need to talk about actions, series of actions and activities. Why? Because I am interested in a non-naturalistic account of artifacts, of course. Intentions as psychological objects must be naturalized. Actions, I believe, resist naturalization. If it is essential for being an artifact that something was produced with a certain intention and the intention is reduced to some neurophysiological processes, then there is no difference between a spoon and a shape sculpted by wind in a rock. Both are the result of different natural processes. We might even say that if we want to scientifically study the production of artifacts by humans and other species (the distinction between artifacts and naturefacts would be only conventional in this case). However the scientific study of artifacts is not the most important activity to which artifacts can belong. It is more important that they belong to activities of production, use (including consumption) and disposal. Descriptions of these activities could be perhaps naturalized, but then we would miss something important. Our qualification of all these as “human activities” would only rest on conventions and accidents, so to speak.

So I think that we should distinguish between artifacts and raw materials, for instance, in terms of the position they occupy in some series of actions. This might seem difficult if we think of cases such as the following. Someone plays with some clay, just to explore the possibilities of building something out of it. The result might be used by another person (or even by the same person), but it was not intended for any particular use. According to my previous attempt at a definition, the thing in case is not an artifact. I do not want to dispute this right now. It can be noticed, however, that the intention to produce something for a particular use seems to be essential in such cases.

So how can the intentions be ignored?

My proposal is not to ignore intentions, but to treat them in a way similar to the one in which they are treated by G. E. M. Anscombe. The presence or absence of an intention has something to do with the larger picture, with the background of an action and with the type of that action (action under a description).

– Thirdly, I think is important that my conceptual proposal with respect to artifacts should be completed by a way in which we could distinguish between what one might call “rule embedding artifacts” and other artifacts. This might be historically relevant, at least, because our societies seem to progress towards being more civilized by producing and using rule embedding artifacts.

The analysis of rule embedded artifacts also provides an interesting occasion to study the relation between natural laws and rules.

[here I include my previous attempts to consider this topic]

How can an artifact embed a rule?

1. Signposts vs. Speed bumpers

A signpost signaling that one should slow down seems to convey the rule that one should slow down at some particular point while driving on the road. Does the signpost also embed the aforementioned special rule? On one hand, we feel inclined to answer in the negative, since the signpost only expresses the rule and we believe that no matter what a rule is, it should not be identified with its expression. On the other hand, since the signpost is at least part of the constraint that one should slow down at some point while on the road (since one could not get a fine for breaking the rule if the signpost were not in place), we might be inclined to say that the rule is at least partly embedded in the signpost.

Of course, the practice of slowing down before pedestrian crossings could function, as it is the case in several countries, without a special signpost being part of it, so the signpost might be regarded as a nonessential part of the rule. Also, if we restate the rule to make the signpost essential – “When seeing a signpost looking so-and-so you should slow down” – it becomes obvious that the signpost does not embed the rule, but the rule regulates its intended use. Thus, speaking in general, we would want to say that sign occurrences do not embed their intended uses.

So much for signposts. Speed bumpers, however, seem to be in a different situation. When placed before crossings, they seem to enforce the rule that one should slow down before a crossing. The problem, in this case, is that in doing so, a speed bumper causes a car to slow down, so we might be reluctant to talk about rules anymore in such cases. A rule is supposed to say what one must do or refrain from doing under certain conditions, but a speed bumper seems to just make something happen.

Perhaps we could pause for a moment at this point and note that what we say about speed bumpers depends on the vocabulary we use in order to talk about the entire situation (this last phrase being used in a neutral way).

We could talk about speed bumpers slowing down cars in a naturalist vocabulary. In this respect, what distinguishes a speed bumper from naturally formed bumps on the road is the fact that the speed bumper was produced and placed on the road by some human agents. The speed bumper is a technological artifact, not a natural object, but in order to function properly it does not need to be recognized as such. In fact, it seems sufficient that it was produced with the intention to cause some effects in the surrounding environment, human beings and their cars included. The intended effects might not even occur. A defective speed bumper is still a speed bumper.

Were we to talk about speed bumpers in a different, non-naturalist vocabulary, we would be saying something different, however. First, we would say that something is an artifact only if it was produced with the open intention to make human agents perform some action – that of slowing down. The open intention, we would say, includes not only the intention that human agents should slow down when meeting a speed bumper, but also the intention that human agents should recognize the intention that they should slow down when meeting a speed bumper. In addition, when speaking about the way in which the speed bumper would make someone perform a certain action we might avoid causal terms in favor of terms like “being responsible for”. Here an objection can be raised, namely that we are not supposed to talk about objects in terms of responsibility, particularly when we explicitly distinguish between “being the cause of” and “being responsible for”.

Responsibility cannot be simply reduced to causal relations, as we can acknowledge from the example of a parent being responsible for the actions of her child without being causally connected with the changes those actions might effect. However, it might seem that we attribute responsibility only to persons and not to objects (or rules, for that matter). This is perhaps due to the fact that we understand “being responsible for action A” as presupposing “being able to admit responsibility for A” as a necessary condition. (I am not saying that someone can assume responsibility only for an action. A doctor, for instance, can assume responsibility for an event – the death of a patient – without being able to indicate any action which she assumes responsibility for. She does not have to believe that omissions are also some sort of actions in order to do that.)

There is, nevertheless, another way in which one could stick to a non-naturalist vocabulary while talking about speed bumpers. The premises of a practical syllogism are not, of course, responsible either for the conclusion of the syllogism, or for my actions, but they can be grounds for a conclusion or an action. The fact that a person accepting the premises might be caused by her acceptance to adhere to the conclusion or even to behave in a certain way does not falsify the previous description. In a similar way, rules can be said to be grounds for actions performed according to them. What the naturalist needs at this point is to specify in which way a grounding relation could hold between an artifact and an action. The problem is that in order to avoid naturalism the grounding relation must be conceived as a logical (or semantic) relation and, as such, for it to hold between two terms the respective terms must have a conceptual content. Here we reach a serious difficulty. Intentional actions can be said to have a conceptual content (see G. E. M. Anscombe, Intention; also, Austin about actions which must occur in a conceptual space in order to be the object of moral evaluations), but it is difficult to see in which way one could say that an object, even an artifact, has a conceptual content.

It seems, therefore, that we have got, although in a cumbersome manner, to the core of our problem. For an artifact to embed a rule it must have conceptual content, so now our question becomes “How can an artifact have conceptual content?”.

2. Being heavy vs. being fireproof

A heavy gambler is similar to a heavy weight lifter. The second lifts heavy weights, while the first gambles large amounts of money, which are supposed to be heavy. Among the uses of “heavy” we can identify one according to which the word “heavy” stands for a natural property. Vague as it can be, the term applies to all things, while being used like this, in the same way. An object is heavy among other objects in terms of the relative weight it has compared to the other objects. A heavy pen weights more than most pens, but it is of course lighter than a heavy piano. Still, for both the pen and the piano, their relative heaviness depends on their weight, which, in turn, depends on their mass and the gravitational field they are in. In order to be heavy an object does not have to somehow incorporate a concept of heaviness.

Being fireproof, by comparison, does not simply amount to having a natural property. Water cannot burn, for instance, but we do not usually say about water that it is fireproof. One could pour water on some clothing in order to make it fireproof for a while, but were we to consider that clothing article we would not simply say that it is fireproof because it cannot burn. We would rather mean that it can protect us from fire. A raw material can be also said to be fireproof, meaning that it can be used to produce a fireproof artifact. When speaking of fireproof artifacts, however, we speak of a way in which they can be used – namely to protect someone or something from being burned. A fireproof safe can be used to protect important papers from disappearing in a fire, for instance. If the practice of protecting things from disappearing in a fire were nonexistent, there would be no fireproof safes. Were we not interested to protect ourselves from being burned, there would be no fireproof things at all. (Also, keeping a one mile distance from a fire can protect someone from being burned, but we do call one mile “a fireproof distance”). In addition, for something to be fireproof it seems important that that thing was produced to be used in a certain way. A wet coat lying on the ground could be used by someone as a protection from fire, but since it was not made for this purpose it cannot be called fireproof.

What can we conclude from this? Perhaps we can say that qualities such as “being fireproof” have indeed a conceptual content, since in order to have them an artifact must have been produced with the intention to be used in some practices composed of actions which do have, in their turn, conceptual content. Does this mean that anything produced with the intention to be used in order to protect someone or something from fire is fireproof? Of course not. In order to protect something from fire a thing must be effective against fire. Conceptual content alone is not enough, of course. However, effectiveness against fire can be described in terms of our actions to protect something from fire being successful. The success of our actions depends on the fact that we act on our environment, an environment which stands, so to speak, outside our conceptual space. In a similar way, the success of our theories depends on how nature really is, but we do not need to (and according to Quine we cannot) talk about “how nature really is” in order to produce and understand successful theories.

[…]

Why should one insist in talking in a non-naturalist vocabulary about artifacts and rules?

3. Fallen trees

Suppose a fallen tree blocks a road. We would not say that the fallen tree embeds the rule that one should not travel that road by using a car. The case does not seem very different from the one in which there was no road to by used by drivers in that place. A fallen tree could, however, be used to prevent drivers to access a certain road, but for it to be used in this way several practices must already be in place. First, we must have the practice of forbidding drivers’ access to roads. Second, we must have the practice of doing so by using barriers (look for the word). Third, we must have the practice of those having the authority to impose such a rule using fallen trees as barriers (a fallen tree could be used like this with the intention to create such a practice, but until the practice exists it cannot be said to embed the rule). Finally, and perhaps the most important, we must be able to regard a fallen tree as a raw material from which we can produce an artifact and notice that raw materials can sometimes become artifacts without any modification (the change of a raw material into an artifact is, in such cases, purely conceptual).

[…]

26.12

One more time.

1) Technological artifacts should not be defined either as some special sort of natural objects, or in opposition to natural objects. [provide reasons]

2) Defining artifacts in terms of intentions does not work properly if intentions are considered psychological states (or acts). […]

3) Raw material, productive action, use (as opposed to “what is it good for”), purpose, techniques (as algorithms), consumption, waste, disposal, recycling… [provide some good and useful criteria or a tentative definition]

4) Discuss about ‘rule embedding artifacts’ (they do not just embed rules for their use, a rule must preexist their production; also, the rule should not disappear after their creation)

A rule can be regarded as some sort of artifact (compare it with a trail in the woods; the rule is not the result of some common behavior; in cases in which the rule is preceded by some common behavior, it looks more like turning the trail into a proper alley in the woods). Rules are not natural, but conventional (and conceptual) – they can function as grounds and make assumptions of responsibility possible (this is disputable).

A rule is like a rail (Wittgenstein). Suppose we decided on the rule that one should only travel on that alley in a vehicle and not wander around. Then the rails could be a rule embedding artifact.

Etc.

But what is the relation between 1-2 and 3? Why do I need to talk about the concept of an artifact in order to define rule embedding artifacts?

Use (for a purpose) – functional properties – actions – actions under descriptions – conceptual content. So artifacts have a conceptual content. So they could embed rules.

So how do they do it?

What is the relation between natural (causal) properties and functional properties?

Lighting a wet candle. Or a fire-retardant material. Fire-retardant (material) vs. Fireproof (object).

Causally exclusive events vs. Opposed actions.

Physical impossibility vs. Conceptual impossibly

How does one become the other?

Quine: it does not. / Sellars: it does (we impose rules on the functioning of objects)

Right, but how? Also: Is this a philosophical problem?

It might not be, but even a scientific research into these matters would require some conceptual effort.

1.01.2014

Let us start from the existing literature this time (see here, for instance):

X is an artifact IFF

(1) There is an A, such that A produces X (an agent, or an author, individual or collective)

However, one may produce something which is not an artifact – a child, for instance, hair (by cutting ones hair), footprints in the sand etc. Now we can argue about the meaning of “produces”, but I do not want to enter into any disputes now – someone produces something IFF that person is responsible (causally, mainly, but not only) for the existence of that thing;

[we could start with ‘A makes X’, which is more problematic, and move to intentional production afterwards]

(2) Given a purpose, P, X could be used to reach P (or X has a function – to be discussed)

A footprint in the sand could be used to identify the person who left it – does this make the footprint an artifact?

(3) A intends X to be used for some purpose, P.

Sure, but X could be broken. Is a broken glass still a glass? Is an expired id card still an id card? Is a broken corkscrew still a corkscrew? We do not need to answer in the same way to all these questions.

Other ideas:

– X is reusable (what about a mold used only once to produce a single statue? – the mold, like the paintbrush, is not a work of art, but a technological object); also, some technological objects (or products – burgers, for instance) seem to be used by consuming them, so they cannot be reused;

– X has some value (if the point is that X has some practical value, then this amounts to (2); if the point is that X has some economic value, then this is not true – I can produce a teabag support out of some cardboard and never sell it as a product; it is still an artifact; if the point is that – X has some value in a different sense, than it is unclear);

– X does not fall under any natural kind (what about salt or glue?)

*

What about the relation between artifacts and human actions?

We can and we do characterize some actions by the type of artifact “essentially” involved in their successful performance (“hammering”). We do, on the other hand, characterize some artifacts by the role they play in our actions (or series if actions). See “can opener”, for instance.

However, we could go in only one of the two directions when trying to say what an artifact is.

*

Saying that social institutions are not natural objects does not seem very useful. The same goes for artifacts (even if not all artifacts have a “social character” – money and ID cards do, toothpicks do not)

My initial idea was: something is an artifact because it figures in some actions and series of actions, usually between procuring raw materials and discarding waste (or consumption).

“But we can study an artifact in the same way in which we study a natural object.” – We can study artifacts as natural objects. The laws of physics also apply to chairs. We might describe and test some physical properties of an artifact, but not in order to produce a theory. We might be interested in artifacts as archaeologists, but this is because we want to learn something about people, not because we plan to offer a theory of artifacts.

So why should we say that this is important for technical objects – that they are not natural objects (although they can be found in nature, since we are also a part of nature)?

This is a sketch of my argument: Rules govern actions, not objects. Some artifacts can embed rules because they have a conceptual content, which they get from the actions in which they are involved.

*

Initial drawing:

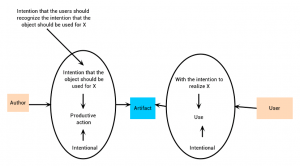

The intentional framework:

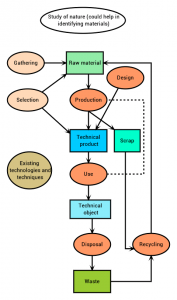

Action framework: